Cities are mankind’s most enduring and stable

mode of social organization, outlasting all empires and nations over

which they have presided. Today cities have become the world’s dominant

demographic and economic clusters.

As the sociologist Christopher Chase-Dunn

has pointed out, it is not population or territorial size that drives

world-city status, but economic weight, proximity to zones of growth,

political stability, and attractiveness for foreign capital. In other

words, connectivity matters more than size. Cities thus deserve more

nuanced treatment on our maps than simply as homogeneous black dots.

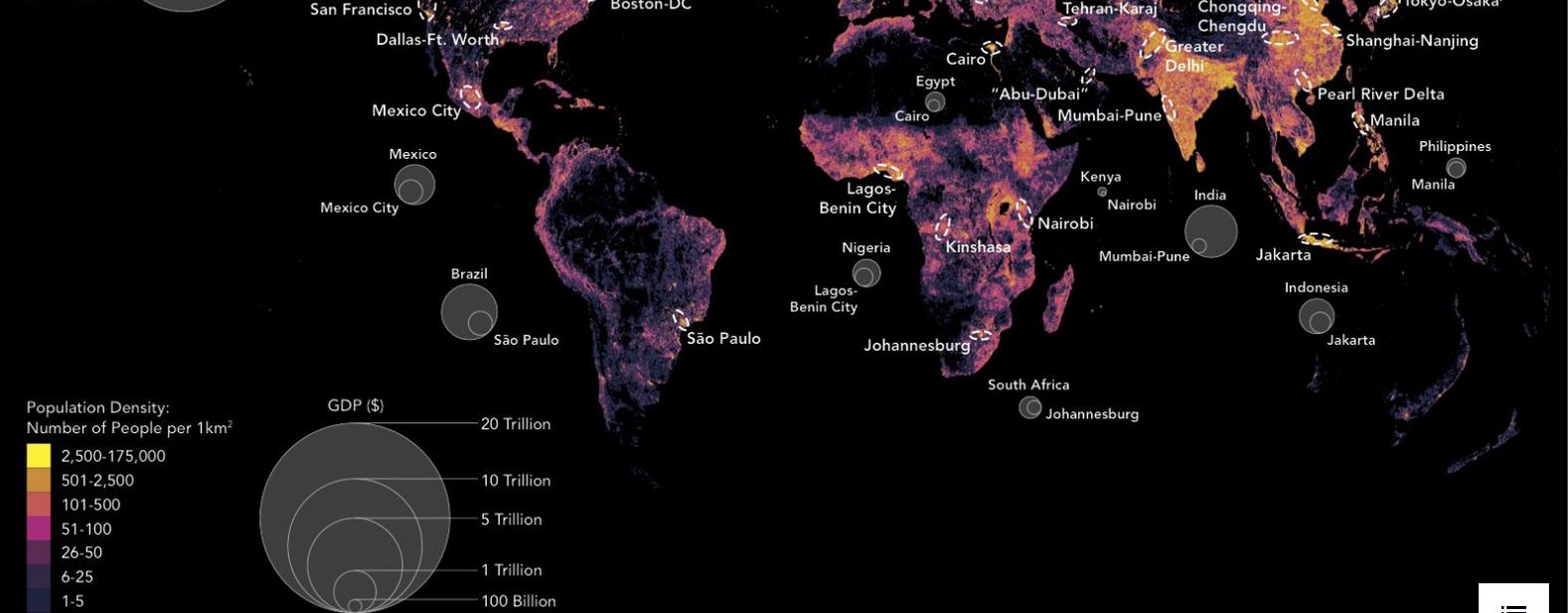

This map from my new book, Connectography,

shows the distribution of the entire world’s population, with yellow

representing the most dense areas. These zones are, not surprisingly,

where you find the dashed ovals that represent the world’s burgeoning

megacities, each of which represents a large percentage of national GDP

(indicated by the larger circles) in addition to its role as a global

hub.

Within many emerging markets such as Brazil,

Turkey, Russia, and Indonesia, the leading commercial hub or financial

center accounts for at least one-third or more of national GDP. In the

UK, London accounts for almost half Britain’s GDP. And in America, the

Boston-New York-Washington corridor and greater Los Angeles together

combine for about one-third of America’s GDP.

By

2025, there will be at least 40 such megacities. The population of the

greater Mexico City region is larger than that of Australia, as is that

of Chongqing, a collection of connected urban enclaves in China spanning

an area the size of Austria. Cities that were once hundreds of

kilometers apart have now effectively fused into massive urban

archipelagos, the largest of which is Japan’s Taiheiyo Belt that

encompasses two-thirds of Japan’s population in the Tokyo-Nagoya-Osaka

megalopolis.

China’s Pearl River delta, Greater São Paulo,

and Mumbai-Pune are also becoming more integrated through

infrastructure. At least a dozen such megacity corridors have emerged

already. China is in the process of reorganizing itself around two dozen

giant megacity clusters of up to 100 million citizens each. And yet by

2030, the second-largest city in the world behind Tokyo is expected not

to be in China, but Manila in the Philippines.

America’s rising multi-city clusters are as

significant as any of these, even if their populations are smaller.

Three in particular stand out. First, the East Coast corridor from

Boston through New York to Washington, DC contains America’s academic

brain, financial center, and political capital (the only thing missing

is a high-speed railway to serve as the regional spine).

From San Francisco to San Jose, Silicon Valley

has become one continuous low-rise stretch between I-280 and US-101 that

is home to over 6,000 technology companies that generate more than $200

billion in GDP (with a San Francisco–Los Angeles–San Diego high-speed

rail, California’s Pacific Coast would truly become the western

counterpart to the northeastern corridor. Elon Musk’s Tesla has proposed

an ultra-high-speed “Hyperloop” tunnel system for this route).

Finally,

the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the largest urban cluster in the

American South, houses industry giants such as Exxon, AT&T, and

American Airlines in an economy larger than South Africa’s and is

actually building a high-speed rail (well, 120 km or ~75 miles per hour)

called the Trans-Texas Corridor that could eventually extend to the oil

capital Houston based on plans rolled out in 2014 by Texas Central

Railway and the bullet-train operator Central Japan Railway.

Great and connected cities, Saskia Sassen argues,

belong as much to global networks as to the country of their political

geography. Today the world’s top 20 richest cities have forged a

super-circuit driven by capital, talent, and services: they are home to

more than 75% of the largest companies, which in turn invest in

expanding across those cities and adding more to expand the intercity

network. Indeed, global cities have forged a league of their own, in

many ways as denationalized as Formula One racing teams, drawing talent

from around the world and amassing capital to spend on themselves while

they compete on the same circuit.

The rise of emerging market megacities as magnets

for regional wealth and talent has been the most significant

contributor to shifting the world’s focal point of economic activity.

McKinsey Global Institute research suggests that from now until 2025,

one-third of world growth will come from the key Western capitals and

emerging market megacities, one-third from the heavily populous

middle-weight cities of emerging markets, and one-third from small

cities and rural areas in developing countries.

There are far more functional cities in the world

today than there are viable states. Indeed, cities are often the

islands of governance and order in far weaker states where they extract

whatever rents they can from the surrounding country while also being

indifferent to it. This is how Lagos views Nigeria, Karachi views

Pakistan, and Mumbai views India: the less interference from the

capital, the better.

It is, of course, very difficult if not

impossible to neatly disentangle the interdependencies between city and

state, whether territorially, demographically, economically,

ecologically, or socially. That is not the point. Across the world, city

leaders and their key businesses set up Special Economic Zones and

directly recruit investors into their orbit to ensure that their workers

are hired and benefits accrue locally rather than nationally. This is

all the sovereignty they want.

To that end, entire new districts (sometimes

called aerotropolises) have sprung up around airports to evade urban

congestion and more efficiently connect to global markets and supply

chains. From Chicago’s O’Hare and Washington’s Dulles to Seoul’s Incheon

Airport, such sites have become the fastest-growing economic

geographies, underscoring the intrinsic value of connectivity. For

companies moving their headquarters into an aerotropolis, the airport is

the gateway to world markets while the nearby city, no matter how

large, is just another sales destination. Recreating the world map

according to the three dozen megacities therefore tells us much more

about where the world’s people are and money is than conventional maps

of 200 separate countries.via

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια :

Δημοσίευση σχολίου